When Pfizer retiree Ira Friedman first joined the company fresh out of graduate school in 1948 in the Brooklyn plant, he had no idea he’d later celebrate the historical significance of a fermentation tank and the opening of an historic exhibit honoring the same place where his 44-year career began.

“I started as a process development engineer in Brooklyn, working in the pilot plant, known as Building 41,” recalled Ira. At the time it was a small scale factory with filter presses, centrifugal solvent extractors, distillation columns and vacuum kettles designed to concentrate solutions at a relatively low temperature to protect delicate products.

“I was totally green when it came to the nuts and bolts of plant operations, but with sympathetic mentors and plant operators, I soon caught on,” said Ira.

With its success in making penicillin during the war, the company used its fermentation know-how to produce a string of antibiotics, including streptomycin, neomycin, polymyxin, bacitracin, and a number of semi-synthetic penicillins. The development group isolated the delicate materials from the fermentation “soup” that contained them.

The plant then ran on three shifts and if there were unanticipated problems with any experiments, which were frequent according to Ira, he and his group responded to the calls at all hours of the night.

When he left Brooklyn for the New York Headquarters and other Pfizer careers, there were two things he was certain of: Pfizer would never stop making citric acid, and the Brooklyn Plant would never close. “How wrong can you be,” quipped Ira?

Ira added, “Because the company was growing then and because chemical engineers can do anything, I had the opportunity to enjoy a long and varied career at Pfizer.” Ira progressed to Director of Process Development and later headed up the Chemical Products Research group, supporting the Chemical Division with home-grown and licensed products for its customers, including flavors, natural food colors, low-calorie food ingredients, a stabilized hop extract for the brewing industry, organometalic products for the plastics industry and “whatever else the licensing group could latch on to,” said Ira.

After an offer from the Legal Division to undertake a new activity mandated by the FDA, Ira initiated Pfizer’s research quality assurance function, with responsibility for independently auditing all preclinical animal drug studies and monitoring on-going operations to assure accuracy and compliance with regulations. “This involved research facilities in Groton, Terre Haute and Amboise, France,” said Ira. His initial staff of two grew to become the Research Quality Assurance Department with on-site inspectors at each location. Ira retired as Director from that assignment in 1992.

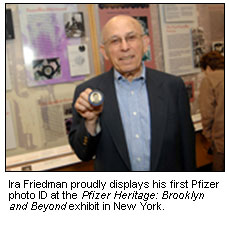

Recently, Ira visited a preview of the Pfizer Heritage: Brooklyn and Beyond exhibit in New York. At the exhibit, Pfizer also celebrated the American Chemical Society’s designation of Pfizer Brooklyn’s innovations in deep-tank fermentation as a National Historic Chemical Landmark.

“There are two Pfizer artifacts I have saved for posterity, my first ID badge (with a full head of hair!) and my napkin ring,” smiled Ira. What significance does the napkin ring hold? Ira explained, “Monthly-paid staff in the Brooklyn plant enjoyed a daily sit-down lunch together in the staff dining room. Each of us had a numbered napkin ring, and the napkins were rotated at random each day so that newcomers could meet other staff members. There was one exception. If then President John McKeen wanted to talk to you, your ring appeared at his table, and you occupied the hot seat!”

According to Ira and other retirees, the Brooklyn plant was like a family. Mr. McKeen knew everyone and got involved with everything. Ira recalled Mr. McKeen visiting the lab just as he proudly finished drying the first kilo of chloromycetin, which they were producing for Parke -Davis. Before Ira could warn Mr. McKeen about its bitterness, he poked his finger in the crystals and tasted some. “Tastes just like brucine”, said McKeen -- brucine being what was painted on kids’ fingernails to keep them from biting them.

Pfizer at the time was manufacturing bulk materials and had not entered into ethical pharmaceuticals. “Our own Terramycin,” remarked Ira, “launched a new era.” The development group was deeply involved in finding ways to manufacture this new product and eventually got involved informally in dosage form testing.

Ira has actively pursued crafts for many years, and since retirement he has continued his craft work. “I have a well-equipped wood shop and have made furniture for our home and our children’s homes,” says Ira proudly. “I’ve often seen pricey things in craft galleries and said, ‘any idiot can do that’, and so this ‘idiot’ learned to work in macrame, stained glass, copper enameling, metal and clay sculpture, water color painting, and most recently Lego mosaics and sculpture.” Ira also enjoys taking care of their perennial gardens and annual flower beds. He is a self-confessed addict of crosswords, Sudoku, Spider Solitaire, Free Cell and their three fabulous grandchildren.

Ira and his wife, Lorry, are two years away from their 60th wedding anniversary. They are active in Temple affairs, particularly the art committee, and have sung in the choir for years. They also sang with the Long Island Philharmonic chorus for several seasons. They are members of several NYC art museums and take advantage of Pfizer’s support of several others. They enjoy the New York theater and traveling, particularly river cruises on small ships.

Finally, Ira offered, “I do our daily cooking and Lorry does the dishes! After all, isn’t cooking simply applied chemical engineering?” Lorry used to kid Ira that his vocation was interfering with his avocations. “I solved that problem by retiring,” laughed Ira.

Click

here to see Ira Friedman's photo gallery.